Shabbat (the Sabbath) is an interesting concept. A day of rest. A day where you don’t do work. A day of reflection. What is it really and what do words like rest, work, and reflection actually mean?

I have never found an interest in ‘keeping shabbat’ (following all the rules) in a strict sense. Not turning on light switches or the using the remote control never made sense to me. Driving isn’t really work, is it? You turn a key or push a button and it starts. After that, what’s the difference? Not turn on the oven or stove. Why can’t I push buttons on the microwave or the air fryer? And not carry? Why do pants have pockets anyway?

When I am in Israel, Shabbat becomes a little bit clearer. I typically find that I look forward to it for a number of reasons. First, by the time Friday afternoon arrives, I am usually wiped out. The thought of having a day with little to do and a chance to really unplug from the prior week is attractive. Going to the Kotel (Western Wall) for Shabbat services is always fun and meaningful. You’ll hear more about that later. A nice dinner with friends that is leisurely and relaxing? Sign me up.

On this trip I had the privilege of learning from three amazing people. As we were walking back to the hotel on Friday after an amazing morning at the Begin Center, I started asking Lori Palatnik, the founder of Momentum, about Shabbat. I understand the prohibition about not working and a day of rest, but my definition of work isn’t starting and driving a car, turning on the stove or oven and cooking, turning on the TV, changing channels and watching shows. So how does that reconcile? Lori taught me something interesting that I am still chewing on. She told me that there is no prohibition against work. That is a wrong interpretation. The prohibition is for creating. And the reason there is a prohibition against creating is that Shabbat is a chance to honor and recognize THE creator, God. The reason she doesn’t do these things is because they involve creating. On Shabbat, it’s all about our creator, God.

It is an interesting concept to take a day each week and use it to honor and thank God. I meditate and pray every day. I have for more than 35 years. I don’t use a prayerbook when I pray, it’s a quiet conversation with God. Over the years it has gone from asking him for things that I wanted to thanking him for the things that I have. When I meditate, it’s often in silence, just focusing on my breathing and paying attention to all the sounds around me. I get in touch with God and with the world. Sometimes I will do a guided meditation to mix it up and they are enjoyable as well. But most of the time, my meditation is about getting closer to God.

So what if I was to expand my practice of prayer and meditation to take a full day each week and focused entirely on that connection with God? I don’t know that I’d go to synagogue or follow a formal process, but what if I were to unplug, honor our creator, and not worry about making anything for a day? It’s an interesting question and one that I will ponder for a while.

I also had the opportunity to learn with Rabbi Yakov Palatnik, Lori’s husband. I have seen him on other trips, but this was the first time I really got to spend time with him, and WOW! I have been missing out. This quiet and humble man is filled with incredible wisdom. One of the things we discussed that really intrigued me was about prayer. As a scholar of Maimonides (the Rambam), he told me that the Rambam said you need three things in a prayer.

The first is to praise God and acknowledge his greatness. While I am not an overly religious person, that is something I always do. One of my favorite things to say is that God often does for me, what I can’t do for myself. I have seen that happen over and over again in my life. Things happen that I hate and that I think are awful and I would get upset about. A few days or weeks or months later, I would look back and realize it was the best thing that could have happened. I know and understand the greatness of God and it centers me and gives me great comfort.

The second is to ask for what you want or need. As I said, I used to do this but stopped. In part this was because of my understanding of the greatness of God. Who am I to ask? I don’t know what’s best for me. Isn’t it better to ask God just to take care of me and that’s enough? Rabbi Palatnik said no. He said we have to ask because we have to know ourselves. If we don’t ask it means we don’t know. Of course God knows, and we aren’t asking for him to know. We are asking to show that we know. We are asking because we have done our part and done the work. That makes sense to me but it is still going to be uncomfortable to ask for things for myself. That is because of the third thing that Rabbi Palatnik told me Maimonides required in prayer.

You have to say Thank You to God. That I do every day. I thank God for giving me another day of life. Sometimes it’s saying the Modeh Ani, but most of the time it is just saying thank you for another day. I say it at night when I go to sleep. I say it throughout the day. Part of the reason I struggle with asking God for things is because I know he will take care of me and I’d rather say thank you than ask for things that I may think I want but in hindsight I wish I didn’t get. Saying thank you to God is comforting to me.

It is an interesting process for sure. Over the next few days, weeks, and month, I am going to follow Rabbi Palatnik’s suggestion to listen to the Rambam. I’m going to work to make sure I include all three components in my prayers. We will see what happens as a result.

The third person I got to learn from was our trip leader, Saul Blinkoff. Saul is an amazing man, and you can google him to learn more about him. During Shabbat, he said two things that really resonated with me.

The first is that what you will die for determines what you live for. It’s a fascinating concept. He shared the story of a woman in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. The woman looked like she was ready to end her life when she walked up to the Rabbi in the camp and asked for a knife. The Rabbi was shocked and worried about her. She demanded a knife again. The Rabbi didn’t have one and tried to talk to her. She looked behind him and saw a member of the SS who had a knife. She walked up to him, grabbed the knife, reached down to her leg and pulled a baby out from under her uniform. She had recently given birth and was keeping the baby a secret. She took the knife, performed a circumcision, a Brit Milah in Hebrew, entering her son into the covenant with God. She then gave the knife and the crying, newly circumcised baby to the SS officer, turned around and walked away. A minute later there was a shot and the baby stopped crying. A few seconds later and the SS officer shot the woman in the back of the head. She knew what she was willing to die for – to be Jewish and part of the Jewish people. So she knew what she was living for.

It is a powerful lesson and question. What am I willing to die for? What is so important to me that I would sacrifice my life for it? I have started my list and will be thinking about this for a long time. Once I know what I would die for, I will know what I live for and can make sure that’s what I am doing in my daily life.

The other lesson Saul taught me on Shabbat was about the mezuzah. I have had a mezuzah on my door for many, many years. I know what it is, why it is there, what is inside it, what it says, where the commandment comes from. One of my clients has a focus on the mezuzah so I’ve learned even more over the past few months. And yet, Saul taught me something new and important. He said that one reason the mezuzah is on the door is because it signals a transition. When we walk into the home from outside, we need to leave our outside problems at the door. It is a visible signal to change our focus to what is inside the house, our family, and go all in. What a really cool concept. A visible reminder of what is important. This is one that I have already started using. When I walk through a new door with a mezuzah on it, I think about where I am going to and what mindset do I need in this new space.

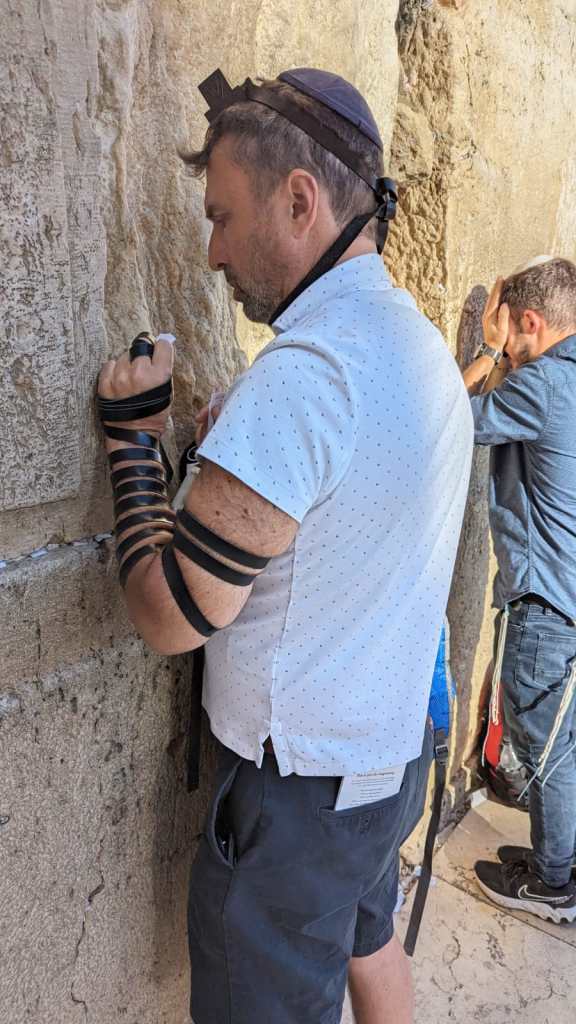

Learning stuff like this to challenge my behaviors and beliefs is really cool (at least to me) but that isn’t the only special part of Shabbat. As I have said, I am not the most religious person and don’t really go to shul. Ok, I don’t go to shul unless it is a family simcha (celebration). In Israel, I don’t want to miss Shabbat at the Kotel (Western Wall). It is joyous, fun, exciting, and meaningful. There are so many different types of Jews there and so many different services going on. And you never know who you are going to see. This Shabbat was no exception. As we got to the Kotel and began our service, I looked ahead and saw Rabbi Lipskier from Chabad at UCF. I quickly made my way over to him to give him a big hug and to wish him Shabbat Shalom. Only in Israel! I returned to our group and the singing and dancing began. We were a group of about 25-30 men. This is small on Friday night at the Kotel but as we sang louder and danced, we started seeing others come over and join us. IDF soldiers in uniform. Hassidic men. Men in Black hats. Men pulling out their kippah from their pocket before they joined us. Men with the big fur hat. Men who looked like they belonged at a Grateful Dead show. Even a little boy. It was amazing to see all these different types of Jews join us to sing and dance.

When it was over and it was just our group again, I started thinking about how this was an allegory for the world. If Jews of all different types can come together at the Kotel on Shabbat and not only pray together and separately but also join together in unification, why can’t we do it elsewhere. Forget about the entire world, why can’t we do this in our local communities? Why can’t we find different types of people who will be happy with their differences and yet also celebrate their similarities? What can we do to make our local communities look more like the Kotel on Shabbat? Different types of people enjoying both their differences and similarities. That’s the type of world I want to live in.

My takeaway is really something else that Rabbi Palatnik taught me during this trip. We have to be able to learn from everybody. It is a fascinating concept that everybody has something to teach us. It doesn’t matter who they are, where they come from, how much or how little they have, how well educated they are or are not, or anything else. Everybody in the world has something to teach us. I haven’t only learned from these three amazing people on this trip. I learned from the other men on the trip. I learned from some of the women on the women’s trip who spoke. I learned from the French Machal soldiers and the families from Kibbutz Alumim who have been relocated. I learned from the farmer, visiting Kfar Aza and Nova. I learned from the Chabad Rabbi who put my tefillin on at the Kotel on Wednesday. When I am open to thing, I can learn from everybody.

What a powerful thought – to learn from everybody and every interaction. That sure makes us all better people and makes for a better world.